Stop running injuries: The 4-week cycle

Running is perhaps the most deceptive of all athletic pursuits. It presents itself as an innate, primal activity—a movement pattern hardwired into the human genome, requiring no equipment beyond a pair of shoes and the will to propel oneself forward. Yet, beneath this veneer of simplicity lies a biomechanical and physiological complexity that makes running one of the most injury-prone recreational activities in the modern world. Epidemiological data consistently indicates that between 20% and 80% of runners will sustain a musculoskeletal injury within a given year.

Fed up of being injured but want to listen to our content? Hit play on the podcast episode below

The central dogma of running injury etiology has long been the phrase "Too Much, Too Soon" (TMTS). This describes a scenario where the imposed demand of training exceeds the functional capacity of the tissues to withstand that demand. While variables such as shoe cushioning, running surface, and foot strike pattern are frequently debated, the overwhelming consensus within sports science is that training error—specifically the mismanagement of training volume—is the single greatest predictor of injury.

Why Do You Keep Getting Injured?

It might not be bad luck. It could be your "Load Architecture." Discover your injury risk score and how to fix your training volume. Start the Free Assessment.

The Physiology of the "Too Much, Too Soon" Trap

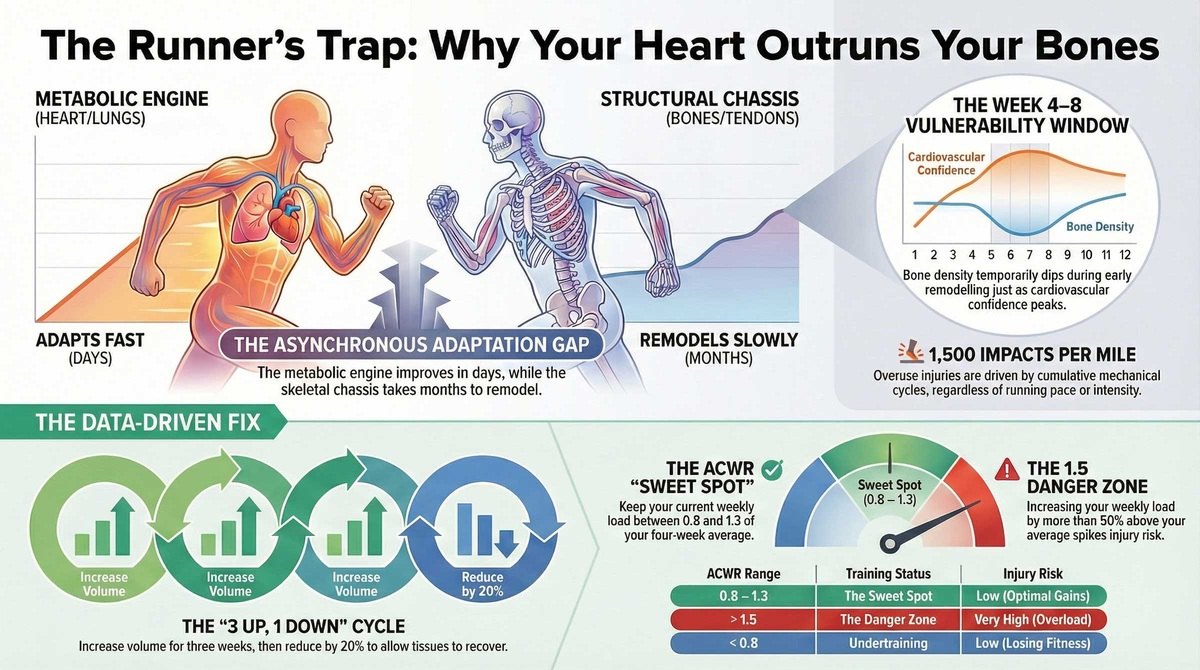

To understand why runners get injured, one must first understand how they adapt. Adaptation is the body's biological response to stress; it is the process by which homeostasis is disrupted by exercise, and the body rebuilds itself to be more resilient to that specific stressor in the future. However, not all physiological systems adapt at the same rate. This asynchrony creates a "lag time" that is the root cause of the vast majority of overuse injuries.

The Metabolic Engine: Rapid Plasticity

The cardiovascular and metabolic systems respond rapidly to stimuli. Within days of starting a programme, plasma volume expands, increasing stroke volume and cardiac output. Skeletal muscle fibres begin to increase mitochondrial density and oxidative enzyme activity within 7 to 10 days. The practical result is that within 3 to 4 weeks, a runner will experience a profound improvement in their "wind" or aerobic capacity. Their perceived exertion drops, and their cardiovascular system sends a potent signal to the brain: "We are fit. We can do more."

The Structural Chassis: The Slow Remodelling

In stark contrast, the structural chassis—bones, tendons, ligaments, and fascia—adapts on a geological timeline relative to the heart and lungs. Tendons and ligaments have a poor blood supply, meaning the turnover of collagen is slow. While muscles may repair micro-trauma within 48 hours, tendon remodelling cycles can take weeks.

Bone is a dynamic tissue, but its strengthening process involves a paradoxical initial weakening. When bone is subjected to new load, the first response is osteoclastic activity—the resorption of bone tissue to remove micro-damage. This is followed by osteoblastic activity—laying down new, denser bone matrix. This creates a "remodelling transient" or a temporary dip in bone mineral density. Typically, between weeks 3 and 8 of a new training block, bone porosity increases. The bone is temporarily weaker than it was at baseline, precisely at the moment when the runner's cardiovascular fitness is encouraging them to increase mileage.

The Physics of Cumulative Load

Running is defined by repetitive impact. With every stride, a runner generates a Ground Reaction Force of approximately 2.5 to 3.0 times their body weight.

-

3-mile run: approx. 5,000 impacts.

-

20-mile week: approx. 30,000 impacts.

-

50-mile week: approx. 75,000 impacts.

Injury occurs when the Cumulative Training Load exceeds the Tissue Load Capacity. In materials science, fatigue failure is a function of the number of loading cycles. Even low-magnitude forces, if repeated often enough without adequate recovery, will cause material failure. This is the definition of a stress fracture: the failure of a material due to repeated cycling at loads well below the material's ultimate tensile strength.

Volume-Dependent Pathologies

Research classifies running injuries into categories based on their primary driver: volume (distance) or intensity (pace). A sudden increase in weekly running distance (over 30%) is specifically linked to "distance-related injuries."

| Injury | Primary Driver | Biomechanical Mechanism |

| Runner's Knee | Volume | Repetitive joint loading irritates the retro-patellar surface. |

| IT Band Syndrome | Volume | Friction syndrome exacerbated by high cycle counts. |

| Shin Splints | Volume | Traction periostitis and tibial bowing from impact accumulation. |

| Bone Stress Injuries | Volume | Fatigue failure where micro-damage outpaces remodelling. |

| Achilles Tendinopathy | Mixed | Driven by both cycle count and high loading rates/speed. |

| Hamstring Strain | Intensity | Occurs during high-speed sprinting due to eccentric overload. |

The #1 Cause of Running Injuries

Are you guilty of "Monster Runs"? Spiking your mileage too fast is the fastest way to the physio table. Check your safety score. Take the Safety Diagnostic.

Deconstructing the 10% Rule

The running community has relied for decades on the "10% Rule": do not increase your weekly mileage by more than 10% compared to the previous week. While this is a useful governor, it has significant mathematical limitations at both the novice and elite ends of the spectrum.

The Floor and Ceiling Effects

For a beginner running 5 miles a week, the 10% rule allows only an extra 0.5 miles—a negligible increase that can stifle progress. Conversely, for an elite runner at 100 miles a week, a 10% jump is a massive 10-mile increase (approx. 15,000 extra impacts), which can be highly dangerous. For elites, increases are often capped at 3% to 5%.

The Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR)

To move beyond linear progression, modern sports science uses the Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR). This compares what you have done recently versus what you have done historically.

-

Acute Load (Fatigue): The workload accumulated in the last 7 days.

-

Chronic Load (Fitness): The average weekly workload over the last 4 weeks.

Formula: ACWR = Acute Load / Chronic Load

The Sweet Spot and The Danger Zone

Research suggests that injury risk is non-linear.

-

The Sweet Spot (0.8 to 1.3): The training stress is high enough to stimulate adaptation but not so high that it overwhelms the tissue.

-

The Danger Zone (Above 1.5): When the ratio exceeds 1.5, you are performing 50% more work than your monthly average. This spike is highly correlated with injury.

The Strategic 4-Week Step Loading Pattern

Continuous loading without unloading leads to accumulated fatigue. Safe volume progression relies on "Step Loading," typically a "3 Up, 1 Down" cycle.

The Mechanics of the Build Block

-

Base Week (Week 1): The foundation established at a comfortable chronic load.

-

Build Week (Week 2): A volume increase of approx. 10% (or ACWR 1.1).

-

Peak Week (Week 3): A further increase of approx. 10%. This is the highest stress point.

-

Cutback Week (Week 4): A deliberate reduction in volume.

The Critical Importance of the Cutback Week

The "Cutback Week" is an Adaptation Week. Physiological adaptation—the actual strengthening of bone and tendon—occurs largely during rest. Total mileage should be reduced by 15% to 25%. This allows the osteoblasts to catch up on bone remodelling and allows collagen synthesis in tendons to outpace degradation. Ignoring this week is a primary cause of the "Week 6-8 Crash," where cumulative micro-damage finally exceeds the fracture threshold.

Specific Tissue Timelines

Different tissues fail at different times. Understanding these timelines allows you to predict and prevent specific pathologies.

The Bone Danger Zone (Weeks 3 to 8)

As osteoclastic resorption peaks before osteoblastic formation reinforces the bone, your skeleton is temporarily more porous. Even if you feel aerobically fantastic, pain during this window—specifically sharp pain on the bone—must be treated with immediate rest.

The Tendon Lag (Months to Years)

Tendons are the slowest adapters. Disuse (detraining) decreases tendon stiffness faster than it decreases muscle strength. Runners returning from a long layoff are at high risk because their muscles can drive them fast, but their tendons cannot handle the rapid loading.

Calculating Your Safe Increase: A Step-by-Step Guide

To safely navigate the volume trap, follow this algorithm:

-

Establish the Baseline: Calculate your average weekly mileage over the last 4 weeks. (Week n-1 + Week n-2 + Week n-3 + Week n-4) / 4.

-

Determine the Ceiling:

-

Novice (under 15 miles/week): Baseline + 1.5 to 2.0 miles.

-

Intermediate (15-40 miles/week): Baseline x 1.10.

-

Advanced (over 40 miles/week): Baseline x 1.05.

-

-

Factor in Breaks: For every week off, reduce the first week back by 20% to 30% compared to your pre-break level.

-

Schedule the Cutback: Mark every 4th week on your calendar as a reduction to 80% of the previous week's volume.

Volume is the prerequisite for endurance performance, but unmanaged volume is the architect of injury. The runner who succeeds is the one who calculates their progression with precision. Respect the lag between your heart and your bones, and treat your rest weeks as a non-negotiable part of your training.

Top 10 Tips

Mind the "Adaptation Gap"

Your heart adapts faster than your skeleton. Don't let fitness write checks your bones can't cash.

Apply a "Penalty"

Reduce your first week back by 20% to 30% for every week taken off.

The "Bone Danger Zone"

Weeks 3-8 are high risk. Bones become temporarily porous before strengthening.

Use the ACWR

Keep your Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio between 0.8 and 1.3 to avoid tissue overload.

Embrace "Step Loading"

Use a "3 Up, 1 Down" cycle. Build for three weeks, then recover for one.

The Non-Negotiable Cutback

Every 4th week, reduce mileage by 15% to 25% to allow structural remodelling.

Respect the "Tendon Lag"

Muscles remember, tendons forget. They have poor blood supply and are the slowest adapters.

The "Slow Mile" Fallacy

Slow running still generates impact. Volume is volume, regardless of intensity.

Rule of 10 Minutes

Starting from zero? Cap weekly increases at 10 minutes of active time, not miles.

Adjust the 10% Rule

High-volume runners should cap increases at 3% to 5% to keep the load manageable.

Top 10 tips for coming back after injury

Returning to the road after a layoff requires more than just enthusiasm; it requires a cold, calculated approach to biology. Use these ten principles to ensure your return-to-run programme doesn't end in another trip to the physio.

1. Mind the "Adaptation Gap" Your cardiovascular system (the "engine") adapts rapidly, often within 3 to 4 weeks, improving your aerobic capacity and making runs feel easier. However, your structural system (bones and tendons—the "chassis") adapts on a much slower, "geological" timeline. When returning from injury, do not rely on how your lungs feel to determine how far you run; your heart will encourage you to run distances your bones are not yet strong enough to handle.

2. Apply a "Penalty" to Your Baseline Do not jump back into training at the mileage you were running before your injury. You must establish a new, lower baseline.

-

The Calculation: For every week you took off, reduce your first week back by 20% to 30% compared to your pre-break level.

-

Long Layoffs: If you missed significant time (e.g., 4 weeks), you should return at roughly 50% of your pre-injury volume and rebuild from there.

3. Beware the "Bone Danger Zone" (Weeks 3-8) Be hyper-vigilant between weeks 3 and 8 of your return. During this period, bones undergo a "remodelling transient" where they become temporarily more porous and weaker before they get stronger. This dip in bone density occurs precisely when your fitness is improving, making it the highest risk window for stress fractures. If you feel sharp, localised bone pain during this window, stop immediately.

4. Use the Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR) To safely manage your return, compare your Acute Load (this week's volume) to your Chronic Load (the average volume of the last 4 weeks).

-

The Sweet Spot: Aim for a ratio between 0.8 and 1.3 to stimulate fitness without overloading tissue.

-

The Danger Zone: Avoid a ratio above 1.5, which correlates highly with injury spikes.

5. Embrace "Step Loading" (3 Up, 1 Down) Avoid linear progression where you add mileage every single week indefinitely. Instead, use a "Step Loading" pattern, typically a "3 Up, 1 Down" cycle. This involves three weeks of building volume followed by one recovery week. This prevents the accumulation of fatigue and micro-damage that leads to structural failure.

6. Make the "Cutback Week" Non-Negotiable Every 4th week, you should schedule a "Cutback Week" or "Adaptation Week" where you reduce total mileage by 15% to 25% (or to 80% of the previous week's volume). This reduction is not a break; it is physically required to allow bone remodelling to catch up and collagen synthesis in tendons to occur. Ignoring this week is a primary cause of the "Week 6-8 Crash".

7. Respect the "Tendon Lag" Tendons are the slowest adapters in the body due to poor blood supply. While muscles may retain strength and "memory" during a layoff, tendons lose stiffness quickly. This mismatch means your muscles can generate forces that your tendons cannot yet withstand. A gradual re-stiffening period is required, often taking months, so be patient with Achilles or patellar issues.

8. Don't Fall for the "Slow Mile" Fallacy Do not assume that running slowly ("Zone 2") means you can run unlimited miles safely. Running is a physics equation defined by cumulative load; a 3-mile run generates roughly 5,000 impacts regardless of speed. In fact, slower running can sometimes increase the time-under-tension and impact peaks per stride, increasing the cumulative load on your skeleton. Volume is volume, regardless of intensity.

9. Use the "Rule of 10 Minutes" for Low Fitness If you are returning from a long injury or starting from zero, measuring volume in miles can be misleading because your pace will be slower, keeping you on your feet longer. Instead, use the "Rule of 10 Minutes": cap your weekly volume increases at 10 minutes of total active time. This accounts for the "time-on-feet" variable which is a better proxy for fatigue in deconditioned runners.

10. Adjust the 10% Rule Based on Your Volume While the 10% rule (increasing mileage by no more than 10% per week) is a useful governor, it has limitations based on your starting point.

-

Low Volume: If you are running very low mileage (e.g., under 15 miles/week), a 10% increase is negligible. You can likely safely add 1.5 to 2.0 miles as a fixed increment.

-

High Volume: If you were a high-mileage runner (e.g., over 40 miles/week), a 10% jump is massive and dangerous. Cap your increases at 3% to 5% to keep the absolute load manageable.

These selections are categorised by their ability to mitigate Ground Reaction Force (GRF), support your "structural chassis" (tendons and ligaments), and reduce the rate of loading on bones during that critical "Bone Danger Zone" we discussed.

The Bone Guardians: Max Cushion and Impact Dampening

Best for: Stress Fractures, Shin Splints, and the "Weeks 3–8 Danger Zone"

The mechanism here is simple: these shoes act as a filter for the cumulative load. By maximising stack height and "compliance" (how much the foam squishes), they dissipate peak vertical impact forces before they travel up your tibia. This is your best insurance policy for protecting porous bone during the remodelling transient.

-

Hoka Bondi 9 The Logic: Think of this as the "Impact Fortress." With a massive stack of compression-moulded foam, the Bondi artificially raises your "Tissue Load Capacity" by isolating your foot from the pavement. Its Meta-Rocker geometry also reduces the active push-off required from your calves, allowing for a protective, low-impact stride that keeps the vibration away from your shins. Target Pathology: Tibial stress fractures, Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome (Shin Splints).

-

New Balance Fresh Foam X More v6 The Logic: If the Bondi is firm and stable, the More v6 is soft and plush. It features the highest volume of Fresh Foam X to date. The extremely wide base provides inherent stability without needing rigid plastic posts, dispersing impact forces over a larger surface area to reduce focal stress on the delicate metatarsal bones in your feet. Target Pathology: Metatarsal stress reactions, generalised joint pain.

-

Brooks Glycerin Max The Logic: A 2026 standout using nitrogen-infused "DNA Tuned" cushioning. It is engineered with distinct zones—it’s softer in the heel to dampen that initial "transient impact" (the first shockwave) and more responsive in the forefoot. This vibration dampening is critical for preventing the micro-damage accumulation that can outpace your body's osteoblastic repair. Target Pathology: Chronic shin splints and heel strike impact.

The Alignment Engineers: Fatigue Management

Best for: Runner’s Knee (PFPS) and IT Band Syndrome

These shoes address the "Adaptation Gap." When your stabilising muscles (like your glutes) fatigue faster than your heart and lungs, your form starts to collapse. This often leads to overpronation or "medial collapse." These shoes act as a scaffold to maintain your alignment when the chassis gets tired.

-

ASICS Gel-Kayano 32 The Logic: The "Smart Scaffold." Instead of a hard plastic block under your arch, it uses a 4D Guidance System—adaptive foam that only compresses when you actually need it to. It specifically counters the fatigue-induced overpronation that happens late in a run, reducing the rotational torque on your kneecap. Target Pathology: Runner's Knee, Posterior Tibial Tendonitis.

-

Brooks Adrenaline GTS 24 The Logic: This shoe features GuideRails technology, which focuses on the knee rather than just the ankle. Think of them as bumpers on a bowling lane; they only engage when your tibia rotates excessively. This reduction in internal rotation is vital for unloading the IT Band and preventing it from rubbing against the side of your knee. Target Pathology: IT Band Syndrome, Patellofemoral Pain.

-

Saucony Guide 18 The Logic: Uses Center Path Technology to cradle the foot with higher sidewalls rather than forcing it into position with a post. It offers a protective, guided feel that is perfect for the "Step Loading" phase where you are increasing mileage and need a safety net against "sloppy" form as you tire out. Target Pathology: Mild overpronation, returning from long injury layoffs.

The Tendon Tools: Geometry and Drop

Best for: Achilles Tendinopathy and Calf Strains

These shoes manage the "Tendon Lag" by altering the mechanics of your lower leg. They are designed to spare soft tissue that hasn't yet regained its full stiffness or resilience after a break.

-

Brooks Ghost 17 The Logic: The "High-Drop Safety Net." With a classic 12mm heel-to-toe drop, this shoe mechanically shortens the calf-Achilles complex. This reduces the "eccentric stretch" (the pulling) on the tendon with every step, "buying time" for collagen synthesis to catch up to your returning muscle strength. Target Pathology: Achilles Tendinopathy, Calf Strains.

-

Brooks Ghost Max 2 The Logic: The "Rocker Offloader." Unlike the standard Ghost, this uses a lower drop (6mm) but adds a prominent GlideRoll Rocker. The curved shape physically rolls your foot forward, doing the mechanical work of propulsion so your ankle and Achilles don’t have to work as hard during toe-off. Target Pathology: Insertional Achilles pain, Plantar Fasciitis.

-

Mizuno Wave Rider 29 The Logic: Another high-drop option (12mm) that uses a bio-based "Wave Plate" for stability. The plate adds a distinct "snap" to the toe-off, reducing the elastic demand on your own tendons. It offers a firmer ride than the Ghost, which is often preferred for protecting the plantar fascia from over-stretching. Target Pathology: Plantar Fasciitis, Calf fatigue.

The Recovery Cruiser: For the Cutback Week

Best for: Easy Miles and the "Rule of 10 Minutes"

-

Nike Vomero 18 The Logic: A maximalist update to a classic. It pairs ZoomX foam (the same stuff in their elite racers) with a massive stack height. The energy return reduces the "metabolic cost" of running, helping you maintain good form even when you are moving at those slow, biomechanically inefficient speeds required during the early stages of rehab. Target Pathology: General fatigue, protecting the structural chassis on easy days.